When I started learning UX, personas were presented as essential. A foundation. Something every designer creates. So I did, without questioning. But the more I looked into them, the more I started to wonder whether they actually help us understand users at all.

What I Was Taught

Personas promise shared understanding across teams. They humanise research data. They give us a "north star" to design for, a fictional character that represents our users. Every course, bootcamp, and case study template treats them as a rite of passage. "Sarah, 32, marketing manager, drinks oat lattes and struggles with work-life balance." I created personas like this for my projects because that's what I was taught to do.

The logic seemed sound: if we all agree on who we're designing for, we'll make better decisions. Personas were positioned as empathy tools, a way to keep real humans at the centre of product development.

Why They Persist

Personas are familiar. They're easy to produce and look professional in presentations. Stakeholders expect a deliverable that resembles "user research." They address a genuine need (team alignment) but not effectively.

According to Nielsen Norman Group, the biggest barrier to adopting better methods is often a previous failed persona effort. Teams dismiss user modelling entirely rather than questioning the tool itself. Many designers, myself included, simply weren't taught that alternatives exist.

What Made Me Question Them

My perspective shifted when I encountered Clayton Christensen's milkshake study.

McDonald's wanted to increase milkshake sales. They had sophisticated customer personas and detailed demographic profiles. They asked customers what improvements they wanted. Thicker? Sweeter? More chocolate? They made those changes. Sales didn't move.

Christensen took a different approach. He observed a McDonald's restaurant for 18 hours, watching who bought milkshakes and when. He discovered something personas had completely missed: nearly half of all milkshakes sold before 8:30 in the morning. The buyers were alone. They purchased only the milkshake. They got in their cars and drove away.

When he interviewed these customers, a pattern emerged. They weren't "milkshake people." They had a job to do: make a long, boring commute more interesting and stay full until lunchtime. The milkshake was thick enough to last the drive. It kept one hand busy. It was more interesting than a silent commute.

Here's what struck me: a 25-year-old tradesman and a 55-year-old accountant shared nothing demographically. Different ages, different jobs, different lives. But they hired the milkshake for the identical purpose. Personas, built on demographics and psychographics, would have segmented them into separate categories. The framework missed what actually mattered.

Christensen also found that the same customers bought milkshakes in the afternoon for a completely different job: a treat for their children after school. Same product, same person, different context, different job. A static persona can't capture that.

What I Now Understand

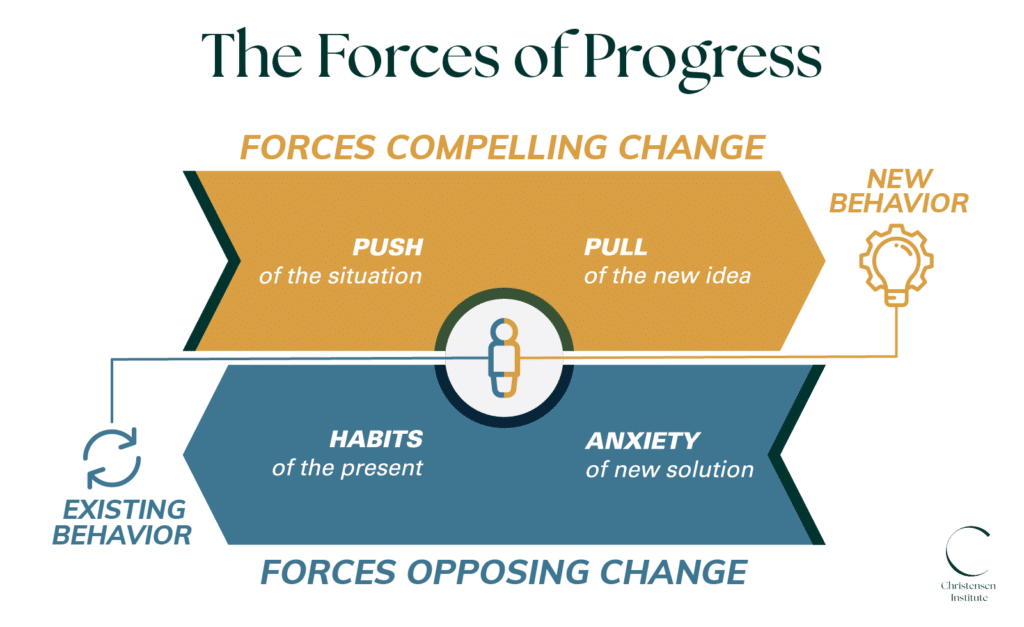

Personas assume that who someone is predicts what they'll do. But behaviour is contextual. Circumstance shapes decisions more than demographics ever could. We don't act consistently based on our age or job title. We act based on the situation we're in and the problem we're trying to solve.

A fictional character frozen in a PowerPoint slide cannot represent the fluid, contradictory, context-dependent ways real people behave.

What I'm Exploring Instead

I've started learning about Jobs To Be Done, a framework that asks a different question. Instead of "who is our user?", it asks "what job are they hiring this product to do?"

JTBD focuses on motivation and circumstance rather than identity. It reveals competitors you wouldn't otherwise see. The morning milkshake wasn't competing with other milkshakes. It was competing with bagels, bananas, and the boredom of a silent commute.

I'm still learning this approach, but the framing feels closer to how people actually make decisions. It respects the complexity that personas flatten.

Where I've Landed

I'm not claiming expertise. I'm still early in my UX journey. But I'd rather question methods now than spend years repeating rituals that don't serve users.

If you're learning UX design, I'd encourage you to look into Jobs To Be Done before defaulting to personas. Ask why someone acts, not just who they are. The answers are more useful and more honest about human complexity.