Users are constantly telling us what they want. They submit feedback, request features, answer surveys, leave reviews. We have more access to user input than ever before. So why does acting on that input often produce mediocre results?

Because what users ask for and what they actually need are often different things. The real job isn't to take orders. It's to interpret. It's to read between the clicks.

The Gap Between Requests and Intentions

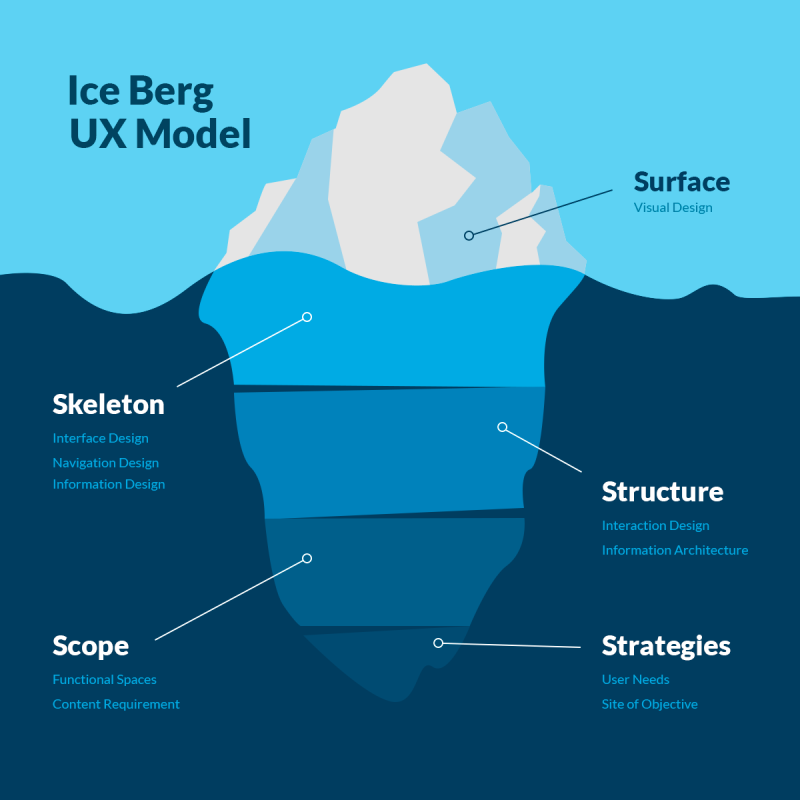

When users give feedback, they typically request mechanisms: specific features, buttons, settings, options. But beneath every mechanism is an intention, what they're genuinely trying to achieve or feel.

Consider music streaming. A user might say, "I want more playlists" or "Give me more ways to organise my library." On the surface, they're asking for more control. But what do they actually want? Probably something closer to: "Help me discover music that fits my mood without spending twenty minutes deciding what to play."

The request points toward more options. The intention points toward less effort.

Seth Godin captures this well. People don't want a quarter inch drill bit, he writes. They want a quarter inch hole. But even that's surface level. They want the hole so they can mount a shelf. They want the shelf so their home feels organised. They want to feel proud of their space. The drill bit is just a mechanism. The intention runs much deeper.

When we design only for stated requests, we miss what's actually going on.

Why Users Can't Always Tell You What They Need

This isn't a criticism of users. They experience problems viscerally, but they don't diagnose them clinically. They know something feels off and propose solutions based on what they've seen work elsewhere.

Think of it like a taxi. A passenger isn't expected to provide the optimal route. That's the driver's job. The passenger's job is to know where they want to go. Good design works the same way: users provide the destination, designers figure out how to get there. Expecting users to hand you the solution is like expecting the passenger to navigate.

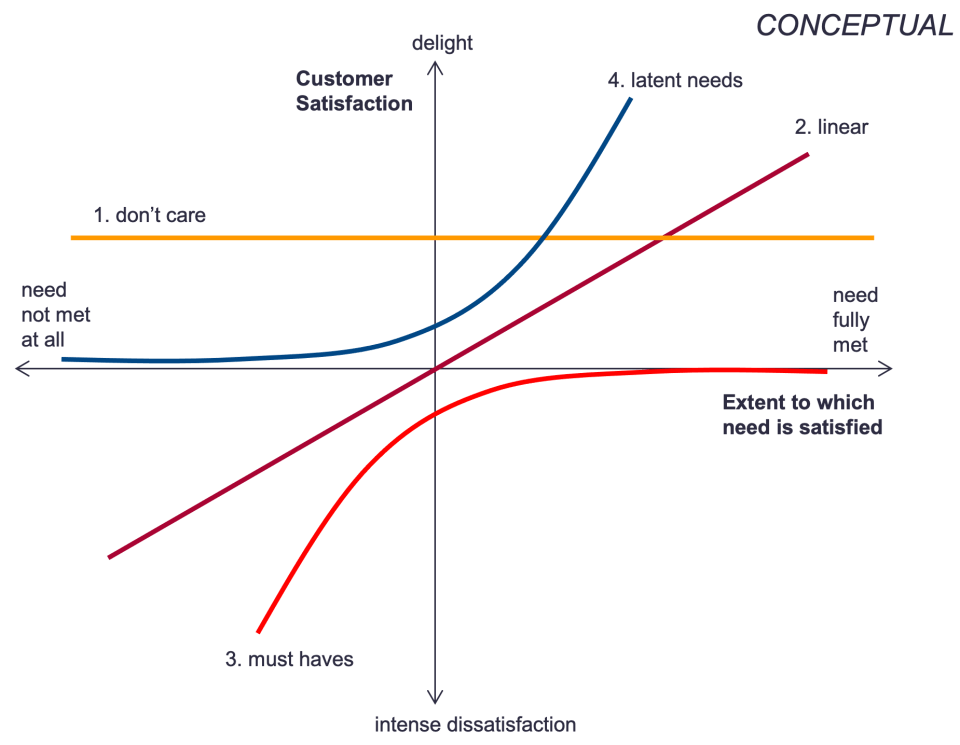

A user overwhelmed by information might ask for "better filters." But what they actually want might be closer to: "Help me feel confident I'm not missing anything important." Filters are one solution, but so are smarter defaults, or surfacing what matters automatically, or reducing the noise in the first place.

The designer who implements "better filters" has followed instructions. The designer who understands the intention has options. And more options usually means better outcomes.

How Do You Uncover Intentions? Start Narrow

Here's the practical challenge: if users can't always articulate what they need, how do you figure it out?

The answer is specificity. The more precisely you define who you're designing for, the easier it becomes to understand their world, their daily workflows, their frustrations, what success actually looks like for them.

Godin calls this the "smallest viable market," the minimum group of people you need to serve to make the effort worthwhile. But it's not just a business concept. It's a design concept. A narrow audience allows you to go deep.

When you try to design for everyone, you're forced to rely on assumptions and generalisations. When you design for a specific group, you can observe how they actually work, notice what language they use, understand what they're trying to accomplish on a regular Tuesday afternoon. The intentions that were invisible at scale become obvious up close.

Specificity isn't a limitation. It's what makes understanding possible.

Observation Over Interrogation

This changes how research works. Instead of asking "what features do you want?" which invites mechanism level answers, you ask "what are you trying to do?" Or better yet, you watch.

How does this person currently solve the problem? Where do they hesitate? What workarounds have they invented? What do they complain about to colleagues but never bother submitting as formal feedback?

Intentions live in behaviour, not in survey responses. They're visible in the friction people tolerate and the shortcuts they create. The job is simply to pay attention.

The Practice Continues

Understanding users is a practice, not a formula. It starts with knowing exactly who you're designing for, then looking past what they request to what they genuinely intend. Getting that right allows design decisions to become clearer, because you're no longer guessing what to build. You're responding to something real.